TRIGGER WARNING – miscarriage, detailed account, pregnancy loss, medical trauma.

How do you begin to explain the toughest thing that’s ever happened to you?

Sitting here at my computer, my hands are shaking and my heart is aching. I consider writing down what happened to me every single day. My emotions have threatened to tear me apart if I write so much as a single sentence. Until today. Three years later.

My miscarriage and medical trauma story

The pain and trauma fester deep down in my soul, and the memories are as real as if they happened yesterday. I suffer from PTSD. I have flashbacks nearly every day. Constant therapy helps me try to process what happened, but at this point, I haven’t even scratched the surface.

But it’s not only the trauma that has kept my story hidden all this time. It’s a sense of being alone in it. I’m reluctant to open up because I feel like no one in the world could understand. Not one person.

Even my wonderful, priceless friends are left lost for words because no one knows what to say. The only person who understands is my husband. We have both felt isolated by our grief and trauma. I can’t vocalise my feelings, because what I experienced seems so far from anyone’s understanding, experience, and even imagination.

Despite having a great support network, this is the loneliest I’ve felt in my entire life. Because going through a miscarriage is lonely. No one gets it. And women are pressured to keep their pregnancy a secret for 12 long weeks, which then results in lots of people going through a miscarriage totally alone.

Even other people who have been through a miscarriage themselves cannot compute because everyone’s personal experience is different. Every loss is so individual.

I’m shaken internally by trauma and grief. But I’m also spilling over with rage, and disgust, over what happened to me and how I was treated. As I share this story and you read through the finer details, perhaps you’ll understand why I feel this way, and I’ll feel less alone. I don’t want any woman to be made to feel the way I did. I am sharing my story also in the hope that it will raise awareness and prevent women being treated this way.

What exactly is a miscarriage?

miscarriage

noun

mis·car·riage ˌmis-ˈker-ij -ˈka-rij, ˈmis-ˌker-ij, -ˌka-rij

1

: corrupt or incompetent management

especially : a failure in the administration of justice

2

: spontaneous expulsion of a human foetus before it is viable and especially between the 12th and 28th weeks of gestation

Corrupt or incompetent management? A failure? I mis-carried? Even the wording is fraught with blame and shame.

Yes, my story is about miscarriage. But actually, it’s not the grief of baby loss that haunts me every day. It’s the trauma and shock of what I went through medically and how I was treated.

Yes, my story is about miscarriage. But actually, it’s not the grief of baby loss that haunts me every day. It’s the trauma and shock of what I went through medically and how I was treated.

Medical Mismanagement

I lost over two litres of blood. I ended up in intensive care.

I was (horrifyingly) awake and conscious through a procedure that went so very wrong.

A procedure that shouldn’t have gone ahead in the way it did.

I lay there with my legs spread and blood pouring out of me, completely alone yet surrounded by the frenzied panic of 16 people struggling to regain control of an emergency situation.

But this was just the end result. I appreciate this is a really long article, but I urge you to (if you are able to) read the whole story, to see the big picture.

It wasn’t just during this horrifying moment, but also through the build-up to it, where I felt I did not receive compassion, recognition, or adequate guidance – all of which I so badly needed.

Perhaps worst of all, none of this needed to happen. The doctors and Early Pregnancy Unit staff had warning signs, which I was verbal about too. They had a detailed account of what had happened so far, yet precautions weren’t taken based on my history.

I don’t want any woman to go through what I experienced. Women going through a miscarriage need to be treated much better. Yes, miscarriages are common, but that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t be treated with dignity and respect.

It has broken me in ways I never knew I could break, and I’m going to spend my whole life trying to put the pieces back together. It has taken away the joy of any future pregnancy (there’s more to that story too). I get traumatic flashbacks and want to curl up in a ball and protect myself whenever I think about what happened.

There is a great deal of focus on the emotional side of miscarriages – and so there should be. The loss, the grief, the mental recovery. But until this happened to me, I had no idea the physical side of a miscarriage could be so horrendous. Women should be warned about this. Educated. Informed about what their bodies may have to go through.

Miscarriage Options: Expectant Management or D&C.

I thought miscarriage was a traumatic, but pretty straightforward thing. It’s not.

Maybe it can be, depending on what route you take and how your body responds, but it wasn’t for me.

I believe that women should be more informed and educated about what their bodies will do, and go through, should they miscarry.

Six months of horror

The process of my miscarriage dragged on for six months. I found out I was pregnant at the end of March, and I was still having scans for retained tissue in OCTOBER. 11 months on. I was told after the miscarriage it was safe to try to get pregnant again – this was incorrect advice. I ended up having my next baby at 28 weeks. But that’s another story which I will write a separate article about. Back to this one.

So you know the end result. I suffered a loss at nine weeks. But how did it happen?

TRIGGER WARNING. There will be some shocking and gruesome details outlined in this story. It’s not for the faint-hearted. It could trigger things for some people. So please only read on if you can handle a very raw and real account of my miscarriage experience.

Where it all began: A pregnancy test

Let’s start at the beginning.

One morning, six months postpartum with my first child, I woke up to blood. Gushing.

I knew something was up, as I’ve always had light periods and have never bled like this before.

So I sent the hubby out for some sanitary pads and a pregnancy test. The worst combination of pharmaceutical purchases for anyone trying to conceive. We did the test anyway. Shockingly, I saw a clear, strong positive line.

There was no normal, overjoyed feeling. We were cautiously happy, but minutes earlier, I’d just had a very heavy bleed – so we knew that plus sign didn’t tell the whole story. We called the doctor and they said to contact our nearest Early Pregnancy Unit.

They said there could be several reasons for the bleeding and that I just had to wait until I could have an early six-week scan. So we anxiously endured four more weeks of worry. I had clear pregnancy symptoms – but continued to have some spotting. I felt sick with worry.

The six-week scan under COVID regulations

We finally got to the six-week scan. Due to Covid restrictions, on the 11th of May, I had to go alone.

I sat nervously in the waiting room, waiting for what could be the worst news, without a hand to hold. I went in for the scan. It was good news. There was a heartbeat.

The sonographer noticed some bleeding on the scan but said it might come out in the next few days without further problems. I saw it with my own eyes on the screen, and tears fell down my cheeks. I immediately rang my husband to share the news. I felt like if there was a heartbeat at six weeks, that was a good start.

Blood and Isolation

From here, things got even more complicated. I suffered another heavy bleed on Sunday the 31st of May.

This was no period-type blood loss; again blood was flooding from me.

I’d already had a child, I’m a woman who has periods – we bleed.

But intuition tells us when things are going wrong, and my heart was in my mouth as we made the frantic drive to A&E, a nappy between me and the passenger seat to try to staunch the constant flow of blood.

With blood still gushing from me, I stood at the hospital reception, alone. Clinicians checked me over and gave me painkillers.

They said ‘You’re most likely having a miscarriage, this is normal.’

The mundanity of it. The patronising tone. How can you deliver such news like that?

It wasn’t the end of my bleeding.

We booked a private eight-week scan for the 9th of July so the agonising NHS wait for the next scan might be curtailed. Despite having more bleeding, I still held on to a little bit of hope – we’d already seen a heartbeat, and after doing some research, I knew some people did experience bleeding and still go on to have a normal pregnancy. I didn’t want to give up just yet.

Private Scan

We went in for the scan and I happily told them that we’d already seen a heartbeat at six weeks.

They began to scan my stomach. A pause. They couldn’t find anything. Slowly my hopes evaporated. ‘It’s going to have to be an internal scan I’m afraid’. So I prepped for the internal examination, knowing they probably weren’t going to find anything.

Thank god my husband could come with me because we’d paid for a private scan. I feel for all the women who got this news alone, due to Covid regulations.

I had friends who’d been through miscarriages. They had told me how unbelievably hard it is to be told this news. But when it happens to you, nothing can prepare you for the emptiness and grief. Nothing. It’s like the whole world swallows you up.

‘I’m really sorry, there’s no heartbeat. You just have a large bleed that’s showing on the scan. This will probably come out soon, so be prepared for an extremely heavy bleed.’

The staff were nice and extremely compassionate as overwhelming sadness engulfed me.

My broken heart shattered at seeing my stoic husband shed a tear in front of the nurses.

We held each other for a few moments and composed ourselves enough to leave the building.

My mum was waiting outside with my seven-month-old in the pram. Because of Covid rules, I couldn’t hug her. Instead, I grabbed up my daughter and held her tight, sobbing into her little chubby face.

The private scanning centre advised that I’d need to be referred back to the EPU to discuss ‘treatment options’. Because it was a private scan the NHS wouldn’t accept it. I had to go back to the hospital to be scanned again, already knowing the outcome. Why was this necessary – all just to fit their records properly?

I had miscarried. But my journey was far from over, and I would have to tread the rest of the path tired and empty from my loss.

A life-altering loss

A few days after my miscarriage was confirmed, I was out walking my two dogs, carrying my eldest daughter in a sling.

All of a sudden, my trousers were soaked.

I felt helpless and sick. I’d stupidly left my phone at home, so I couldn’t call my husband for help.

I was stranded, with green fields as far as the eye could see. How was I going to make it home?

I waddled along cautiously, taking tiny steps to try to stop the progress of the blood which was coursing down my legs.

With relief, I reached the path. Two elderly ladies stopped and said how adorable my little girl was.

Embarrassed, I had to interrupt, to tell them that I was having a miscarriage and was bleeding a lot.

These women were wonderful. They insisted on walking me home, even though they couldn’t walk very far themselves. One of them told me how she’d had a very serious ectopic miscarriage, which was why she’d ended up adopting.

Thanks to those lovely ladies, I made it home safely and my husband was able to look after me.

We ended up in hospital again, where they checked my bloods for infection and then sent me home. Again, “ It’s all normal and just part of the miscarriage”. Unexpected physical trauma was only compounding the grief.

Punished by protocols

As I mentioned earlier, because it had been a private scan where my miscarriage had been confirmed,the EPU needed me to have ANOTHER scan with them, to ‘confirm’ things.

So with the copper taste of dread in my mouth, I booked and attended this scan, already knowing the bad news. I sat in the waiting room alone. Due to Covid, I was forced to do this without anyone there to support me (like many other women). My tummy empty, surrounded by other happily pregnant women, awaiting official NHS confirmation of my baby loss.

After the scan confirmed what we already knew, I had to talk with the consultant about how to manage the miscarriage.

I went into the room and sat down. The consultant looked up from her screen, and asked, ‘Are you aware of what they found on the scan?’ Of course, I was. ‘Yes, there was no heartbeat, I’m having a miscarriage.’

She then hit me with an unexpected bombshell.

She said, ‘On the scan, they found two sacks.’ Wait, what? I realised what she was telling me. I had lost twins.

A wave of emotion crashed over me. Two. I had lost two babies.

The hardest part? Calling my husband from the hospital to tell him the news. It’s not fair he had to receive the news like that, from his broken wife.

I know him so well, and I could hear that knowing there had been two took him over the edge. We were both lost in a new wave of grief, tumbled by the sadness for what could have been.

After this call, the nurse sent me to a quiet room on my own so I didn’t have to sit sobbing in the waiting room of pregnant women. I sobbed for a good 20 minutes, waited until I felt strong enough, and then went back to the consultation room to discuss my options.

Miscarriage (mis)management

I had talked to my husband and some friends who had some helpful advice. I’d done my research. I’d decided that ideally, I’d like to have the operation to get it dealt with quickly. I wanted to be awake for the procedure if possible because the recovery is faster (no anaesthetic), so I’d be able to get back to my daughter sooner. Or so I thought…

Alone, but one of many

One recurring theme of this experience was that the staff made this earth-shattering loss feel unimportant and every day, continually stressing that it happens to lots of people. A message that I suppose was meant to impart comfort just left me feeling misunderstood and as if I was overreacting to this life-changing grief.

We discussed my options. The nurse stressed that they were trying to avoid operations due to Covid. That I should at least try ‘expectant management’. What a pragmatic term for the horror of waiting for your dead baby to be naturally evacuated by your body, over a period of days or weeks.

If that doesn’t work, she said – take the tablets which help it pass. The implication was that, if I didn’t follow the advice here and choose one of these two options, I was being unnecessarily awkward and difficult.

Miscarriage management through medication

I was physically and emotionally tired, from the grief and the bleeding was a constant reminder of what I was going through.

I didn’t have the mental strength to sit around and wait for the foetus to pass. No, thank you.

I just wanted to get it done.

The EPU nurse suggested that the operation I had chosen as the best course of action for me wasn’t really an option at all. I should have pushed for what I wanted and what I deserved, despite it being “difficult” for them during Covid circumstances. But I was weak and bent over with grief. I was vulnerable. So, reluctantly, I agreed to give the tablets a go. That was a bad decision.

Uncomfortably known as “the abortion pill”, this combination of misoprostol and mifepristone cause the foetus to be evacuated, much like a “heavy period”. Except it’s not, or it wasn’t for me. Women should be made aware of just how much blood can leave their bodies in a very unnerving way.

The shocking reality of medical miscarriage

Because we have to choose a course of action, I feel that those suffering pregnancy loss already “have enough to think about”. So we don’t ask about the reality of what’s ahead.

What I really want people to understand about taking these tablets is that it’s an extremely unpleasant and scary experience.

Much more than “quite a heavy period”, an “uncomfortable” experience where you “might bleed quite a lot”, and “might need to lie down for the day”, the process is, in essence, medically provoked intense contractions.

Perhaps it’s not the same for everybody. But I’ve since spoken to other women who have tried this route, and they’ve all said it was so much worse than what they had prepared themselves for.

Emergency interventions

I went home and took the tablets to bring on the miscarriage evacuation. I waited.

After about two hours, it began. I remember calling my friend from bed, telling her I felt sick, hanging up, and rushing to the toilet.

Instead of sick, copious amounts of bright red blood gushed from between my legs.

I remember looking down thinking maybe I was wetting myself.

But no, it was blood.

I still remember the horrible sound it made, hitting the porcelain.

Within minutes the whole downstairs bathroom was covered in blood. We’d been prepared for “a heavy period”. I remember panicking, asking my husband ‘Is this normal? How much blood is normal?’

Pains shot through my stomach and the blood continued to flow as we realised I needed to return to the hospital.

I tried to make it upstairs to change into fresh clothes. I crawled up the stairs in agony, like a wounded animal. But I didn’t make it to the bedroom. I collapsed on the bathroom floor. As I floated in and out of consciousness, a pool of blood formed around me. Like something out of a horror story.

My husband stood by me holding our baby girl whilst trying to call an ambulance. I looked up at her thinking, I can’t believe she’s having to see her mummy in this state.

I was still conscious at this point, so I was “not a priority”.

The ambulance took half an hour to arrive. They assessed me and decided to take me to hospital, so I was helped into pyjamas and helped out of the front door and into the ambulance.

I’d never been in an ambulance before. I’d never been to the hospital before.

This was absolutely terrifying for me. And I had to do it alone because my husband wasn’t allowed to come.

I got to the hospital and they checked my bloods and vitals again. Everything was OK.

But I was not OK. I was traumatised by what had just happened. So was my partner who had looked on, helpless, holding our baby, as I lay bleeding and waiting for medical help.

As I write this I still can’t believe that this wasn’t even the worst part. I haven’t even gotten to the most difficult part of the story.

The agony continues…

After taking the tablets, you have to wait three more weeks to confirm your situation by doing a pregnancy test.

If it’s still positive, you have to go back. Again.

Of course, my test still showed positive. I had to go back for yet another scan, to see what was going on.

The sonographer could see there was still a huge, ominous pool of blood and tissue in there. Every scan showed this large pool of blood. I felt anxious about it, but no clinician voiced any concern.

It was Monday, August the third, and the scan confirmed I’d either have to take the tablets again or have the op.

Well to hell with the tablets. By now, my only option to complete the miscarriage was to have the operation.

Yes, the operation I had decided was the right course of action TWO MONTHS AGO. I went through this hell, unnecessarily, to arrive at the same point. Completely unnecessary suffering.

As I said, I’d researched. Being awake for this op means you can recover more quickly. That’s because you don’t have to go under General Anaesthetic (be “knocked out”); instead, they use a Local Anaesthetic injection to the areas involved.

But if I’m honest, I was also scared of the (albeit small) inherent risks of going under General if I didn’t have to.

Looking back, with all of the bleeding episodes and the ominous pool of blood seen on every scan, clinicians should surely have been prepared for me to bleed. And I should’ve been made aware of this…in which case I might have chosen not to be awake through the living nightmare which was to come.

I can’t help but blame myself a little bit, for making such a bold choice to have the operation whilst awake. But I was broken in so many ways and wasn’t really thinking straight.

I was expecting, like most surgery, that I’d have some wait, but no. They could fit me in for the procedure that same afternoon. I think they had a cancellation and it was convenient for them to squeeze me in quickly. Perhaps they put convenience before safety.

I wanted this hell to be over, so, of course, I went for it, returning at 4 pm. A matter of hours. Flustered, I called a friend and acted brave, saying in a trembling voice, “It’s fine, I can do this”.

A waking nightmare

I was going to be awake. I knew what was to come; they would insert a tube into my uterus and suck “everything” out of me.

I had to keep the word “babies” at bay; this was medical now and I had to approach it pragmatically if I was to get through. I had to be brave.

Before the procedure, you have to take the same tablets that I had taken before. I questioned this – these tablets had made me bleed profusely to the point of collapse. But they reassured me the same wouldn’t happen.

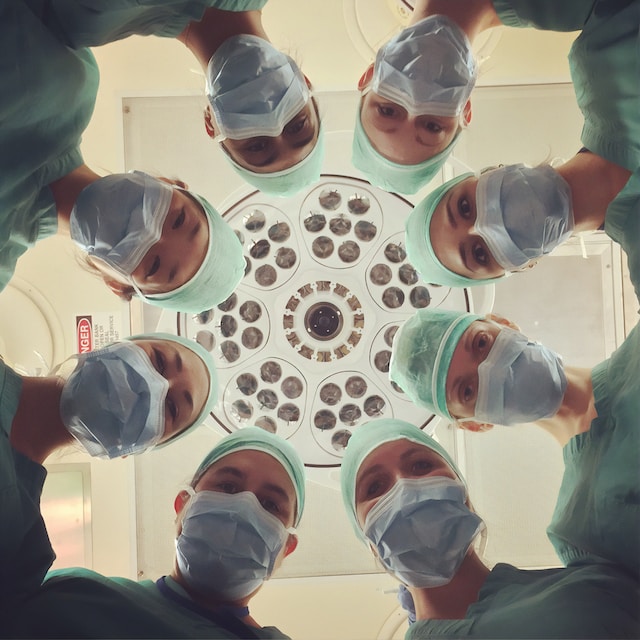

I walked into the room where the doctor and a few assistants were waiting.

I clocked the spread of tools on a table – clinical, but as terrifying as something from a scary film scene – so tried pointlessly to turn my attention elsewhere. I lay down, feeling so ultimately vulnerable as I spread my legs with my feet in the stirrups, and waited for the procedure to start.

Perhaps it wouldn’t be so bad.

I kept chatting away to the nurse to try and distract myself from what was happening. I could vaguely feel things coming out of me, but it wasn’t too painful.

I looked up at a painted mural on the ceiling and tried to take my mind elsewhere. To a place where I wasn’t having nine-week-old twins removed from me whilst I was awake.

As things went on I started to feel the sensation of more hot gushing blood flowing out of me. It felt so strange and so wrong.

They offered me Entonox, the ‘gas and air’ to take the edge off the pain. I willingly obliged. All of a sudden the atmosphere changed in the room. I felt the focussed calm turn to panic in my slightly spaced-out state, as clinicians rushed into the room.

Just breathe in and out. Focus on the gas and air. Try not to pass out. You need to stay conscious, I thought. My survival instincts were kicking in.

I asked the staff what was going on and they said ‘You’re losing some blood, we just need to try to control it.’ I knew it hadn’t yet been controlled because I could feel it leaving my body, along with all the pregnancy tissue. I couldn’t see it – but I could feel everything.

From this point, it went downhill. I later found out that 16 people were in the room. Faceless people tried to stick numerous needles into me, without much success, but I didn’t care about this discomfort – I just focused on staying awake.

I started to panic, repeatedly asking the nurse beside me ‘Am I going to be OK?’ She tried to reassure me, but her eyes told me that things were bad. ‘Please, get me back to my daughter. I can’t be taken away from her.’ I begged. I suddenly felt overwhelming desperation to get home to her. She needed her mummy. I had to survive this.

I heard shouting around me. I was told they were going to need to take me to theatre, immediately. I was going to be put under General.

“Please just put me under”, I said. “I don’t want to have to witness this anymore”.

But it wasn’t that simple. I was on the EPU ward.

This should’ve been a fully functioning ward, but it wasn’t at the time, because of Covid. They just weren’t prepared for this to happen to me, and I wasn’t in the right place to get the treatment I required.

I was eventually rushed out of the room on a gurney. On the way out, they crushed a nurse in the doorway, and she fell over and injured herself. I later found out she had been off work for a few weeks because of it. That’s how frantic the situation was. They took a nurse out amidst the chaos.

They wheeled me through the hospital to the theatre, whilst trying to keep me stable, and the last thing I remembered was lying on the theatre table.

The edge of life itself

The doctor said to me, “We’re going to put you under to control the bleeding. Try and think of something nice.”

This is perhaps the part that haunts me the most. At that moment, I knew there was a chance I might not wake up. It sounds dramatic, but it was very real.

A weird sense of calm came over me. I thought about my husband and daughter, and I said to myself ‘at least I have loved.’

I knew that I’d loved my husband and daughter with all my heart and therefore if it was my time, I’d lived a happy life. I closed my eyes thinking of them, as everything went black.

As I came around from the procedure, I seemed to wake for a few seconds, suffer a wave of nausea, then pass out again.

This happened several times until I was sick, and I came to a bit more.

I remember waking up screaming, asking for more pain relief. It was a nasty way to wake up, but all I was thinking was “If I’m throwing up, and in pain, I must be alive”. Thank god. I would see my husband and daughter again. I would hold my baby girl. I would never let her go.

I remember dazedly thanking the doctors and nurses for saving me and wanting to hug them.

I don’t remember much after that, until I awake properly – in an intensive care room with needles sticking out of my arms.

In hindsight, I wonder if my recovery was more painful because I later found out that they had scraped into the muscle tissue too far during the procedure.

This was knowledge I wasn’t party to until later, when my second daughter was born at 28 weeks. Her premature and dangerous arrival, wrought with illness, was probably due to the internal damage done to my tissues during this op.

It was very scary waking up here in the ICU. I quickly realised I had a catheter in, and also something else down there.

The doctor came in and explained that they had put a balloon up inside me to stop the blood haemorrhaging. A balloon? Really?? I had lost over two litres of blood and had multiple blood transfusions.

The balloon they had put in place was the only way they could control the bleeding. So I still wasn’t out of the woods, then.

They would have to let the balloon down slowly, a little every few hours. Each time, they would need to check there wasn’t more bleeding until they could eventually take it out.

It was nerve-wracking. We didn’t know, each time, whether letting the balloon down a little would result in more bleeding.

Alone under constant care

No one was allowed to visit me because of Covid. However, because I was still breastfeeding my eight-month-old, they let my husband bring her in twice, just so that she could feed.

They told me I should consider stopping as I was so low on blood and energy. That it wasn’t wise. But I didn’t want to take that from my daughter, and after everything that had happened, I didn’t want the ability to breastfeed to be taken away from me, either (thankfully I was able to breastfeed her until she was 18 months old in the end).

So I sat in my intensive care bed and breastfeed my daughter, crying as I held her in my arms.

I had to try to stop her from grabbing all the canulas, and needles that were stuck into my veins. But I was just glad to hold her again. I was a complete mess. I think it was pretty shocking for my husband to see me looking this way, decimated and alone on an intensive care ward.

Reliving Historical Fears

I had to have a further blood transfusion whilst I was awake. Nothing really, for most people. But for me, this was terrifying. My father had a blood transfusion before they screened the blood properly. Thirty years later, he died from liver failure as a result of the Hep C he caught via the transfusion. You can read his story here.

I knew I needed the blood to help me get back to full strength. But I cannot explain how horrible it was for me to watch someone else’s blood drip into me, knowing that this is what killed my father.

I cried and cried as I lay there for an hour waiting to receive enough blood. I yearned for comfort from my family – the only ones who would understand – but I was alone. I explained to the nurses the connection, but they still struggled with why I was so distressed.

Over the next day or so, I remained stable. Bit by bit, they were able to remove the balloon with no further bleeding. After two days in intensive care, I was sent to a normal ward to recover further.

The doctor told me the op was as much of a success as it could be, considering they were trying to stop the blood. They had tried to remove as much tissue as they could, but because it was an emergency situation they couldn’t guarantee they had removed everything.

Basically, they were telling me that, despite everything I had already been through, there might still be some miscarriage tissue left. I could not believe it. It wasn’t over. I just wanted to move on and I couldn’t. I felt imprisoned.

Whilst I was recovering, I received a guest. A lovely anaesthetist came to see me. She was crying. She said to me how horrified she was by how things had gone.

This shouldn’t have happened the way it did, she said, and she felt so bad. Finally, a human. A genuine human, apologising for a system in complete breakdown.

An overloaded, underfunded system full of great people who are stretched to breaking point every single day, and find themselves in situations that are unsafe, and with outcomes they can only be ashamed of. The ward I was on should’ve been fully functional, but Covid had put paid to that. They didn’t have the staff. They weren’t prepared for an emergency like mine.

I went home and began the process of trying to put myself back together. I was a mess physically. I had no energy. I had headaches and nausea for weeks because of the antibiotics. The recovery at home was very slow going. It would be weeks before I could even go for a gentle stroll.

Seven Scans. A Succession of Failure

I miscarried in June. On Monday the 3rd of August I had the operation. The last, and seventh, scan I had (where they confirmed I still had some retained tissue) was on the 8th of October.

There still seems to be no clear–cut end to this process. The scans continue mostly without much drama, and without much optimism on my part.

At one scan, a trainee (I hadn’t been asked, by the way, if it would be ok for a trainee to complete the scan) was prodding around nonchalantly.

She clearly had something on her mind. Finally, she made her excuses – she had to rush, as she had to pick up her children from school. Maybe not the best topic of conversation for a woman at a miscarriage scan?

At a follow-up, private gynae appointment, I spoke to the Head of Gynae at Haywards Heath Hospital. He knew my story. As if I was a celebrity case; a case which went so spectacularly wrong that word had gotten out.

Perhaps I was a training example. “What would you do if your ward was understaffed, and an unexpected haemorrhage happened to a patient in your care?” If my story is so well-known, why haven’t I received any sort of an apology?

Because of the nature of what happened the hospital booked a follow-up meeting with the doctor who performed the operation and the uncaring nurse who managed the whole process.

It was too soon after the trauma. My husband and I went in unprepared, only to be fobbed off and lied to about the extent of what happened. They were clearly trying to cover their backs instead of apologising and being compassionate. There was no accountability. I wish we could do this meeting again because at the time I wasn’t strong enough. I had no fight in me to challenge them.

Thank goodness this is not the end of my story. I am now the mother of two beautiful daughters, or four, including the twins I lost so early. My second beautiful baby, despite her very early arrival, is now fit and well (after a horrendous two years of being in and out of the hospital all the time).

However, the negligence I’ve been faced with continued through my following pregnancy. I was told specifically that it was safe to try again, despite having retained tissue from the miscarriage. I was never informed of any risk to future pregnancies.

My daughter Jovie arrived, in a whirlwind of shock and panic, at 28 weeks.

Thank goodness, due to medical advances over the past few decades, she was viable for life outside the womb.

But she needed a hell of a lot of help at the beginning. Following her birth, I suffered from retained placenta. In-camera images, the doctors saw profound intra-uterine scar tissue, which they said was likely the result of the miscarriage procedure scraping too deep into my muscle tissue.

This would’ve weakened my placenta and resulted in my daughter’s premature birth.

She suffered from chronic lung disease and went through multiple, prolonged hospital stays when she arrived, as well as both baby and me suffering from sepsis prior to her birth and nearly dying. Ten long weeks in the hospital following her birth, six of these spent on an intensive care baby unit (NICU). We battled for her entry into this world and for my right to remain. I will tell her story separately when I’m ready.

These chronicles perhaps aren’t over, though I can only wish they were.

My only hope is to open the eyes of other pregnant people suffering in the same situations and faced with the same options.

As patients, we should have agency. We should be heard. We should be treated as humans. These are the three profound elements of my care that were missing. And that’s why I tell this story now – and seek, this time, to be heard.

If you’ve made it to the bottom of this article, thank you. I am so grateful you’ve taken the time to read my story. Please raise awareness. Please share this with others. Please start conversations and campaigns that will change the way women go through miscarriages. This isn’t right.

*This article was edited by Phoebe Ryan.